Business Opportunities Seen in New Tests, Low Scores

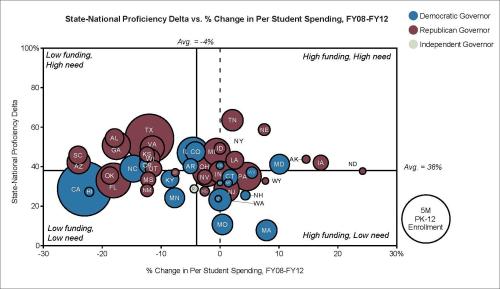

(Source: Parthenon Group, via National Center for Education Statistics; Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; National Governors Association.)

If the chart above appears only to be a mess of undecipherable bubbles, look more closely (or just enlarge the thing). The man who prepared it, Robert Lytle, a head of Parthenon Group’s Education Center of Excellence, sees a business opportunity.

I’ll explain. The chart shows all 50 states plotted based on two factors: the state’s change in per-student education spending, and the difference between how many students scored “proficient” on state tests vs. national tests. The size of each bubble is based on population. A state like California, a populous state that is slashing its education budget but rates its students relatively in line with the National Assessment of Educational Progress tests, goes in the bottom left. A state like Tennessee, where education spending increased between 2008 and 2012 but state test scores wildly overrate students compared with NAEP, goes in the upper right.

It’s in the states in the upper right that the best business opportunity—for both for-profit and non-profit investors, publishers, vendors, and, most importantly, education service providers—can be found, Lytle said.

Those states are among the few actually finding some money. Those are also the states most likely to perform poorly on the upcoming assessments based on the Common Core State Standards, adopted by 45 states. As my colleague Andrew Ujifusa wrote in June, some states are preparing for the common assessments by increasing the rigor of their existing state tests—the large variances in state proficiency requirements are well-documented— but there’s the potential for serious gaps in the early going. An example: Florida tweaked its Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test and 4th graders dropped from 81 percent proficient to 27 percent in one year on the writing test.

“I would anticipate that the performance is going to be poor, if indeed you have a state where they’re making a pretty big shift in expectations,” Kathy Christie, a vice president at the Denver-based Education Commission of the States, told Andrew. (I highly recommend reading Andrew’s piece for more on changing and varying state academic standards.)

So, Lytle reasons, those states suddenly looking at much lower test scores are going to need some help in improving them.

“The market is heading toward big performance gaps,” Lytle said recently in New York City, at a one-day conference on private equity and the education industry that I attended. (Read more about the conference in this article by Reuters.) Parthenon is a global consulting group headquartered in Boston; its education practice counts government agencies, school districts, and education service providers as clients.

When presented to the room of investors at the conference, this chart blew most people away. Those in education know how variations in funding and assessment create 50 different business climates for which companies must adapt. So to simplify things like Lytle did—though it’s never that simple—gave investors hope that a sector notoriously fickle and recently bearish might not be so bad. Especially for companies focusing on these three priorities:

- curriculum—what is being taught?;

- pedagogy—how is it being taught?;

- and human capital—who is teaching?

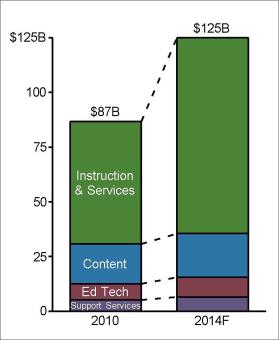

To the left is another chart that supports that theory. The commercial education market grew significantly in the past four years, but no segment grew faster than instruction and services. Think companies like virtual learning providers K12 Inc. and Connections Academy, or publishers-turned-service-providers Pearson and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (education publishing sales, by contrast, are down from $8.2 billion in 2008, to $7.1 billion in 2011, Parthenon estimates).

While his audience in New York City consisted mostly of for-profit ventures, Lytle told me any group that convinces education officials it can help improve performance will find opportunity.

“Anybody with the ability to help close the performance gap, they are willing to talk to you,” Lytle said.

(Source: Parthenon Group, via U.S. Census Bureau; E-Learning Council; National Center for Education Statistics; BMO Capital Markets; Simba; Company Financials; Company Earnings Calls; Analyst Reports; Veronis Suhler Stevenson.)

(Source: Parthenon Group, via U.S. Census Bureau; E-Learning Council; National Center for Education Statistics; BMO Capital Markets; Simba; Company Financials; Company Earnings Calls; Analyst Reports; Veronis Suhler Stevenson.)There are, of course, two ways to take advantage of these opportunities. A vendor can offer a product or service that is rigorously proven to improve academic results, so convincingly that districts can’t help but purchase it. Or, as is sometimes the unfortunate case, they can make headway without proving anything.

Companies with great academic results have succeeded, and so have companies with poor results. But the former strategy is expensive for companies, because it requires a lot of product development, third-party research, and a close relationship with districts. From the customer side, schools may struggle with implementation of new products and not see the vendor’s intended results, Lytle said.

Diane Ravitch, an education advocate and vehement opponent of for-profit education, doesn’t have much confidence that schools’ best interests will be considered.

“The bottom line is that they’re seeking profit first,” she told Reuters.

Whether or not that’s true, how will these market forces affect what actually ends up in the classroom? For one, Lytle said, consolidation of the industry is “inevitable,” possibly leaving districts with fewer choices.

Companies with large sales forces will be able to better pinpoint the local opportunities and pitch their wares. And as more service providers enter the market with unique technology, the larger companies will snatch them up to integrate with their own products.

In a couple years, the existing “$5 to $20 million companies won’t be around,” Lytle told the group.

Within the education market, there is another line of thinking, championed by investment groups like NewSchools Venture Fund and Imagine K-12: that the opportunity in education is for startup companies taking a teacher-centric approach, winning customers through product development, not sales forces. In that world, the bigger companies fear the startups, they don’t necessarily buy them. Perhaps that aligns with bigger ideological differences between Silicon Valley and Wall Street.

Either way, with opportunity comes activity and there seems to be plenty on the horizon.

Read Parthenon’s presentation, “Balancing Opportunity and Risk in K-12 Publishing.”

There’s still the danger of post hoc fallacies from looking at data at the 50,000-foot level, which, of course, has never stood in the way of ginning up demand for a product or service.

This paragraph bothers me a little:

"There are, of course, two ways to take advantage of these opportunities. A vendor can offer a product or service that is rigorously proven to improve academic results, so convincingly that districts can’t help but purchase it. Or, as is sometimes the unfortunate case, they can make headway without proving anything."

The former seems much less likely than the latter.

I am glad that a description is given of start up school reform companies with a teacher/school centered approach.

An approach that includes creative product development, access to leading scientific research and a reputation for quality customer service will attract and retain customers because of the results they receive.

The difficulty comes in sorting through the products and services that are available and identifying the teacher/school centered companies.

Bill Younglove

8:21 AM on August 9, 2012

Oh mi’gosh, how is a teacher to sort out exactly which vendor will serve his/her students’ increasing their academic achievement the most? Oh, wait, I forgot that that is not the teacher’s job, just as it was not his/her place to be consulted in a meaningful way about the curriculum, not to mention considerable pedagogy these days, in the first place…Bill Younglove 🙁

Schools are not cash-cows. As a society, we do not benefit by turning our public educational system into a painted lady for the edu-pimps as described in this article. Has anyone taken the time to consider what our society will look and function after 20 years of these destructive policies? We had better. Ever-increasing teacher turnover, shoddy pedagogy, fluid administrative leadership and massive edu-huckster influence will undermine our nation.

I added this to the following blog post:

Common Core Costs Too High, Failure Guaranteed

http://radicalscholarship.wordpress.com/2014/03/04/common-core-costs-too-high-failure-guaranteed/