U.S. ‘Education Efficiency’ Ranks in Bottom 50 Percent, Study Says

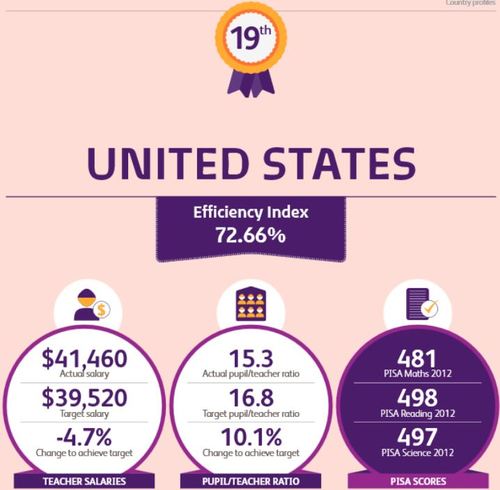

The U.S. ranks 19th out of 30 countries in the outcomes it gets from its investments in education, according to “The Efficiency Index: Which education systems deliver the best value for the money?,” a report released Thursday by GEMS Education Solutions, a London-based education consultancy.

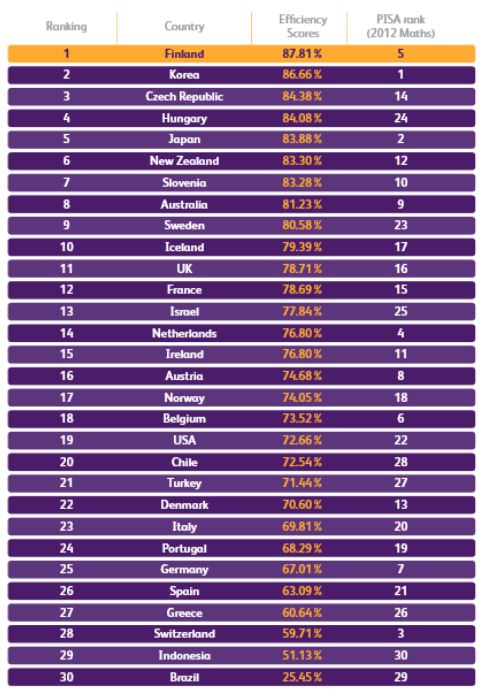

Finland, Korea, and the Czech Republic were deemed the most educationally efficient countries in the study, which is based on 15 years of data from members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Researchers used composite achievement results from the 2012 Programme for International Student Assessment, or PISA, as the performance metric, and weighed those scores against 63 “inputs,” or factors that could influence educational outcomes, such as teaching materials and technology, the quality of school buildings, and teacher training.

Only two factors in the statistical model were found to have an impact on PISA results: changes in teachers’ salaries and class size. The United States would have to reduce teacher salaries about 5 percent below their current average of $41,460 and increase class size by 10 percent—to nearly 17 students per teacher—to be optimally efficient, the researchers said.

The performance differences among the countries “cover less than a quarter of the variability in outcomes that are observed between schools and pupils,” acknowledged Andreas Schleicher, the director for education and skills, and special advisor on education policy to the secretary-general of the OECD, in his introduction to the report.

For instance, socioeconomic differences among students in various countries were not considered, said Adam Still, a co-author of the report and an education finance and development specialist for GEMS, in a phone interview. Rather, they focused on factors that education policymakers could influence, he said.

However, Schleicher wrote that the efficiency index is important because it “breaks the silence on the efficiency of educational services,” and raises questions about what is possible for improving educational return on investment during tight budgetary times. Some of the countries with the highest efficiency ratings do not pay the highest salaries, nor do they have the lowest student-teacher ratios.

“Korea and Finland are at the top. They, relatively speaking, have large class sizes. They both pay moderate wages by comparison, and wind up on top of the rankings,” said Still. “If you visit those two systems, they will look and feel quite different, but both achieve highly in terms of PISA scores.” In fact, five of the top 10 countries in the efficiency index are also in the PISA top 10—Finland, Korea, Japan, Slovenia, and Australia.

Near the bottom of the efficiency index are countries such as Germany (25th) and Switzerland (28th), which rank seventh and third, respectively, using the PISA score metric. In those countries, increasing the relatively high salaries for teachers would not improve student performance.

Countries can be inefficient for underpaying or overpaying teachers, the study indicates. Brazil (30th on the list, and 29th for PISA), like Indonesia, is inefficient because its low pay for teachers makes it difficult to attract them. The report’s authors conclude that modest extra expenditures in those countries would result in “significantly” better educational outcomes.

The full efficiency index rankings are available here:

Still, who holds a masters degree in mathematics from Oxford University, and is a graduate of the Teach First program in the U.K. (an across-the-pond cousin of Teach For America in the U.S.), said the econometric analysis applied to the OECD data is “relatively advanced, well-trusted and valid.” It is used in other industries and sectors, which have also been held up to standards of performance basedon metrics. (Here’s an international study on efficiency in health care systems, for example.)

“We’re not directly prescribing that these changes should be made,” he said. Rather, it’s a lens through which to evaluate education. He equated it to the concept as it applies in the automotive industry. “If it wasn’t for the car industry striving for fuel efficiency, it wouldn’t have innovated to produce hybrid cars. If you don’t hold up a lens, maybe you don’t find reasons to innovate,” he said.

Alas, in July, the U.S. also ranked low in an international innovation study based on data from OECD countries.

Credit: Infographic and Efficiency Table are from The Efficiency Index: Which education systems deliver the best value for the money?

Who gives a you know what about this study? Just because some geeks can peg a number to something, doesn’t mean anyone should care. Cut staff and lower pay … great advice! That’s what teachers want to hear right now. The only reason why I’m wasting my time commenting on this is because there is some egghead administrator or school commissioner or politician out there saying to himself, "Hmm. I see the light! I’ll pay my teachers less, increase their class sizes, improve efficiency, get higher PISA (and TIMSS?) test scores, save America from all that ails it, put every single student in college, watch them all graduate and get jobs paying six figures, and have statues erected in my honor."

I may be exaggerating, but probably not by much. Is that you sitting there reading this and thinking those kinds of thoughts? Do yourself a favor and go talk to a real teacher. He or she will set you straight.

As usual when we look at "averaged" class sizes it presents a distorted picture. There are NO classes with 17 in my entire district of 11,000 students except for special education classes for kids who have severe learning disabilities and other challenges.

We also cannot, I repeat, CANNOT compare US schools to Korea or other nations because the systems are simply too different, apples and oranges comparisons never work. I also argue with the word "efficiency"! I’m not interested in producing cars or manufacturing widgets, I work with children who don’t do well on an assembly line!

These kids of nonsense studies are simply ways for otherwise useless people to try to prove their usefulness by creating "studies". Let’s stop wasting time and money on these worthless comparisons and focus on creating high quality schools with great facilities, highly trained staff and REGULAR EDUCATION class sizes capped at 25. Then you can compare me to anyone because I will, as will my teaching colleagues, blow you out of the water with what we can do given the right materials.

"They both pay moderate wages by comparison, and wind up on top of the rankings."

The above statement suggests that the U.S. could lower rates of pay to mirror their moderate pay. But there are considerable social benefits to living in Finland. In South Korea, this is less true, although they are further ahead in universal healthcare. Such social benefits are a major consideration in rate of pay. I think the authors of the study might want to try living on $39K and change and see how they like it.

Honestly, I am sure these guys are very fine statisticians but we should be focusing on improving instructional practice and student learning that counts rather than data points that don’t inform much. I have poured over PISA released items for years and am not sure that this is the one "shining beacon of light" we want to have directing us toward our future in education. I question whether PISA or TIMMS really assess what we value as learning in the US. Measurement should fit instruction and not vice versa.

One more, "let’s punish teachers" solution is not useful. in our country a $41,000 salary is certainly modest. I can just envision who will take this report out of context and start proposing legislation! Yikes!

Who thinks it’s valid to conclude that policymakers can’t impact socioeconomic status? Oh, right, everyone who thinks poverty has nothing to do with outcomes.

I don’t claim to know whether teachers make more or less than they should, but this study is absurd. Simply because they measure efficiency in ‘outcomes’ on a standarized test relative to teacher salary and class size is completely meaningless except in the context of their statistical model they’ve designed.

It has no bearing on reality because it isolates variables that appear to have a correlation, but that correlation may be coinciental–there is nothing in the study one thing causes (or has anything) to do with the other, except they are parts of a whole. That has no practical application at all–in spite of the researchers claiming that it does.

In the end, I’m less concerned about efficiency and more concerned about quality. The fact of the matter is that, while resources are limited and scarce, that is a matter of societal priorities–not necessity.

Didn’t Aristotle say, ‘What is honored in a country is cultivated there’? We pay a lot of lip service to honoring education, but the actions of our policymakers tell a much different story.

I would find it hard to find a school district where class size averages 17 students…AND as the economy improves, districts will find it increasingly difficult to attract, let alone retain, the best and brightest to the teaching profession. So on its face this study is ridiculous…at perhaps based on faulty data. 17 student class average…what a joke! try 30 to 40 in most urban classrooms!

Who are they counting as teachers? And how are they counting classroom size? Around here, K-1 classes are over 25 students and older grades are as many as 35 students/class.

Maybe we could make teachers more efficient by removing all the ridiculous test prep curriculum, and go back to good old fashioned "let the teachers teach!"

And while we’re at it, let’s let the gifted kids move up to the right level academics, whether through grade or subject acceleration. It’d be a lot more efficient to let them move on when they already know the material, rather than spending years reteaching them the same stuff.

Just an idea…

Teaching and learning are the primary issues that matter in a classroom; but learning NEVER occurs without students knowing that their teachers CARE about them. These kind of data (showing care) are what matter in a classroom–bot these data presented in this manuscript. If "care" seems a little "soft" when it comes to genuine data that matter, that’s faulty thinking–care always matters–at every grade level and with each student. So, guess what larger class sizes do to CARE and TEST SCORES–makes them both negative aspects of learning. Of course, how would a "graduate" of "teach for America" (researcher in this alleged study) know anything about care . . . because he only received 6 weeks of training to become a teacher Want to know what matters in a classroom–teachers who care! Measure that and you’ll see gains in learning–not test scores–learning! See the book, Why America’s Public Schools Are the Best Place for Kids: Reality vs. Negative Perceptions by Dave F. Brown.

Let’s require a HS diploma, lower teacher pay to the minimum wage and increase class size to 50. Then we’d really be efficient.

Terribly mindless empiricism leading to simply dangerous conclusions

The child poverty rate in the U.S. is roughly quadruple that of Finland–of course education is "less efficient" when you’re paying for cure instead of prevention. That doesn’t mean educators are doing anything badly or inefficiently: it means the underlying political and social situation is broken to begin with.

A more accurate analysis would be to say it’s impossible to compare the efficiency in countries like the U.S. and Finland because it’s an apples and watermelons comparison–only Romania has a child poverty rate higher than ours, and the OECD average on the PISA is half of hours. Really high child poverty rates means lots more special education and remediation, which costs a ton more.

Also, if you were analyzing the "efficiency" of the various systems in promoting economic growth, you’d RAISE teachers’ salaries, because that would boost demand (the middle class and working class are totally tapped right now), which would be the most efficient way to grow the economy. (Notice also that this efficiency calculation would have to be different for nations with different levels of wealth and income inequality, because in very unequal nations such as ours, the "efficient" policies are those that channel more money to the poor and middle class, but the opposite would be true in a country where the economic pie were divided too equally).

Finally, there’s no evidence that international test scores predict national outcomes for highly developed countries such as ours(1), so why are we pretending PISA test scores tell us what we need to know? Most of what matters for individuals and nations simply isn’t on the tests.

1) Francisco O. Ramirez, Xiaowei Luo, Evan Schofer, and John W. Meyer, "Student Achievement and National Economic Growth." American Journal of

Education: 113:1.

used to treat malaria chloro https://chloroquineorigin.com/# hydroxychloroquinine