Assessing the State of the K-12 Testing Market, As Dynamics Shift

There’s an assumption that a lot of people have been making about testing in the common-core era that goes something like this:

As states have scrambled to roll out high-stakes online exams aligned to the standards, the testing industry has reaped the benefits. Companies have reeled in huge contract after huge contract, creating a frenzy of not just competition but also profit, with taxpayers picking up new, daunting costs amid the gold rush.

But the reality appears to be more complicated than that.

In Education Week’s most recent issue, I explored the recent decision by McGraw-Hill Education to get out of the state- and summative-testing business, and what the move says about the industry overall. One of the takeaways is that while the state testing market over the past few years has been good to some companies, there’s little evidence that overall profits in that area have surged as a result of common core assessments, as some observers (particularly critics of the common core) have claimed.

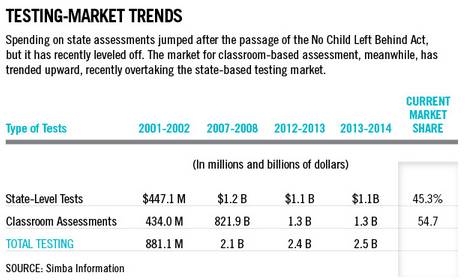

Consider the data. Over the two most recent available years, when states, with the help of federal dollars, were immersed in crafting assessments aligned to the common core, state testing revenues remained relatively flat, at around $1.1 billion, according to Simba Information. That contrasts pretty sharply with the period after No Child Left Behind took effect, when the state testing market soared, from $447 million to $1.2 billion in just six years.

The real area of growth for the industry has come in a different area of testing entirely—classroom assessment, where revenues have risen from $434 million to $1.3 billion in 12 years, creating a market that now surpasses the state testing arena in size. See the breakdown below:

Classroom assessments tend not to be high-stakes, strike-fear-in-the-heart-of-the-school-community brands of tests. In fact, they include formative assessments—on-the-fly measurements of student learning designed to shape instruction, which tend to be popular among educators.

These numbers will probably leave some readers puzzled, as data that contradict prevailing narratives often do. How can the market for state testing have flatlined, with so many states adopting new, common-core aligned exams that cost many millions of dollars to administer?

One explanation is that much of the new money being poured into new, common-core tests is, in fact, not new money at all.

While it’s true that states are spending huge amounts of money on testing—California recently hired the Educational Testing Service for $240 million; New York spent awarded Questar $44 million to work on a subset of state exams—what’s crucial is that for the most part, that’s money that states were already spending on testing, well before the common core came around. In other words, in many states, policymakers have simply replaced their old assessments with new ones. It just so happens that the new ones are aligned with the common core.

What’s less clear is where the market goes from here.

It’s possible that states’ spending on state tests will fall, as states that are working together share costs. States belonging to the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers, or PARCC, last year awarded a contract to Pearson to cover an array of test administration and delivery work. The other main state consortium, Smarter Balanced, is leaving much of that administrative work to its individual state members.

Then again, as my colleagues Catherine Gewertz and Andrew Ujifusa have reported, even as states work together on testing, a review of the nationwide map (see below) reveals that the state testing market has become fragmented in recent years, as states have abandoned PARCC or Smarter Balanced, or while keeping ties with those consortia, have moved ahead with creating and paying for exams on their own.

All this is not to say that certain vendors haven’t done quite well in the state testing market over the past few years. ETS recently swiped a cluster of state testing awards in proudly anti-common core Texas, worth an estimated $280 million, from Pearson; it also recently won the $80 million-per-year testing deal in California, fending off McGraw-Hill Education/ CTB and Pearson to hold onto a contract it already had. And major testing vendors snatched up a lot of the $360 million in federal funding that supported the development of the two main state consortia’s common-core tests.

But smaller, and less-prominent companies have also notched, or are poised to win, big state deals, including the aforementioned Questar and Data Recognition Corporation, which is taking over McGraw-Hill Education’s state and summative testing work.

It’s a bit unclear, however, just how much money there is to be made in state testing, and whether profits outweigh the risks for some companies—such as a high-profile foul-up that brings embarassment or even a demand for restitution from a state client.

In an recent interview, McGraw-Hill Education CEO David Levin declined comment on the how profitable the state testing business has been for his company, as it leaves that arena. But he said the number of vendors jostling for state contracts tells you that the “business is sustainable,” and that there is “price tension between multiple players.”

“I don’t think there are extreme margins being made in that space,” said Levin, whose company intends to re-focus on instructional resources, adaptive and formative testing, and other areas.

What’s also unclear is how the recent wave of anti-testing sentiment among some parents and policymakers will sway the state market.

Assuming that Congress, despite the anti-testing backlash, does not upend the requirements for state exams found in the current version of the No Child Left Behind Act, the answer may be “not much.” Which would leave the market for state testing in much the same place that it is now—not too hot, not too cold—but more or less holding steady.

See also:

Sean, you nailed the pivot point in your last paragraph–politics. I’ve been in assessment for a decade and a half, and I’ve been watching NCLB and its impact on education since it was implemented. You (and your readers) may recall that NCLB was up for renewal in 2007, but Bush threatened to veto the renewal that Congress was pushing, so Congress decided to wait until the next presidential election to try again. Well, the economy crashed and NCLB stayed as is. Now, in 2015, Obama is threatening to veto the latest NCLB renewal a year before the next presidential election……deja vu, anyone? If NCLB doesn’t pass this year, the testing will continue unabated until the new president puts together their educational plan and gets it through Congress. Since the Republicans will almost certainly retain control of Congress in 2016, which party controls the White House will determine how the next chapter of NCLB renewal is written. Too much can change between now and 11/8/16 to make any worthwhile predictions of what a president from either party is likely to do with testing–we can only wait and see.

This is really a easy step which we can take every time with the http://freerobuxgenerator.net. Here you cna make lots of possible ways quickly. Thanks a lot for provide the quick options.

Now you can easily take steps to get some free money on roblox and earn some free robux thought free roblox generators.

As states have scrambled to roll out high-stakes online exams aligned to the standards, the testing industry has reaped the benefits.