Most Ed-Tech Products Don’t Meet Minimum Criteria in Their Privacy Policies, Report Finds

A study by Common Sense finds that only 10 percent of the more than 100 ed-tech applications and services evaluated by the organization met minimum criteria for transparency and quality in their privacy policies.

The research uncovered what Common Sense called “a widespread lack of transparency, as well as inconsistent privacy and security practices” in its three-year review of how student information is collected, used, and disclosed on some of the most popular applications and services in education technology.

In this research, “transparency” refers to whether the ed-tech providers are open about disclosing certain practices, or whether they explicitly allow those activities, including third-party marketing, behavioral advertising, tracking users, or creating profiles for the purpose of advertising.

The selection of the 100 ed-tech companies was based on reporting from about 140 schools and districts in a consortium that works with Common Sense, as well as identifying some of the most popular products in online stores and those listed on the Common Sense site.

“It’s vital that educators, parents, and policymakers engage in the same conversations with the ed-tech industry that we’re having now with Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and other social media platforms about building solutions that strengthen our children’s security and privacy protections,” said James P. Steyer, founder and CEO of Common Sense, in the announcement about the white paper’s results.

From the ed-tech industry perspective, the analysis can help companies improve, said Mitch Weisburgh, the co-founder of Academic Business Advisors, LLC. and the current president of the Educational Technology Industry Network of the Software & Information Industry Association. Common Sense provides “an incredibly valuable service by independently reviewing education tools,” he said in an email response to an inquiry about the report.

“As they mention in their opening paragraphs, privacy and security are horribly complex. Their guidelines and reviews can also be used by the companies who were reviewed to help them ensure that their policies and procedures are in place to protect children,” he said.

“There’s a lot to unpack here,” said Linnette Attai, president of PlayWell LLC, a privacy and safety consultancy that helps companies with compliance. “Everyone has improvements to make, for sure.”

However, Attai cautioned that “it’s not a sign that vendors are doing anything unethical,” adding that “omission [of information from a privacy policy] does not mean misbehavior. It should mean behavior that’s not taking place.”

The 2018 State of EdTech Privacy Report was the first on this topic, according to Girard Kelly, counsel and director of the privacy review for Common Sense, a nonprofit that provides ratings and reviews of ed tech. In 2019, the organization plans to repeat this study, expanding its outreach and identifying by name all the applications included in the review—since their grades will be listed on the site, Kelly said.

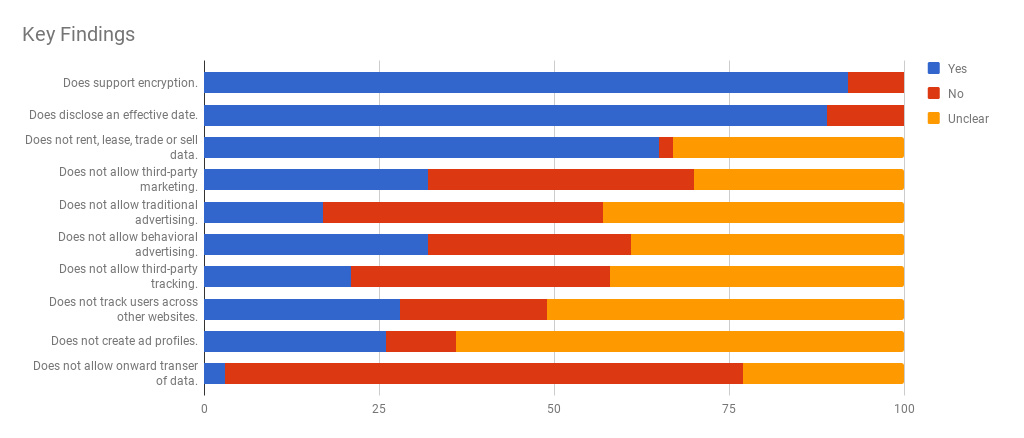

According to Common Sense, almost all the ed-tech applications and services it evaluated either do not clearly define safeguards taken to protect child/student information, do not support encryption, or lack a detailed privacy policy. Co-authors Kelly, Bill Fitzgerald, and Jeff Graham’s key findings include:

- Third-party marketing raised red flags: 38 percent of educational technologies evaluated indicated they may use children’s personal and non-personal information for this purpose.

- Advertising within the context of displaying content: 40 percent indicate they display contextual advertising based on the page content, and 29 percent indicate they show behavioral ads based on the child’s usage of the service.

- Web-based services and tracking: Among web-based services, 37 percent indicate that collected information can be used by tracking technologies and third-party advertisers, 21 percent indicate the collected data may be used to track visitors after they leave the site, and 30 percent ignore “do not track” requests or other mechanisms to opt out.

- Creating profiles: 10 percent report that they create profiles of their users.

- Right to transfer personal information if company’s ownership changes: Nearly three-fourths (74 percent) indicate they maintain the right to transfer any personal information they collect if the company is acquired, merged, or files for bankruptcy.

- Moderating social interactions: Only 11 percent indicate they moderate social interactions between users, and 14 percent say they review user-generated content to remove materials that are inappropriate, such as gambling, alcohol, violent, or sexual content.

- A public lens: Half of the ed-tech products reviewed allow children’s information to be publicly visible.

“It’s somewhat surprising to me that they found any percentage of companies that are targeting children and showing behavior ads based on a child’s use of services,” said Attai, who also serves as the project director for the Consortium for School Networking‘s privacy initiative. “It demonstrates a certain ignorance to the requirements,” she said.

Another way of expressing some of the organization’s findings is in the following chart, highlighting the percentage of responses for each of 10 key findings.

Privacy Evaluation Initiative

The report is based on research from the Common Sense Privacy Evaluation Initiative, which breaks down complex privacy policies to help educators make informed choices to protect student information online. The privacy team goes beyond the requirements of the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA), the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), the Protection of Pupil Rights Amendment (PPRA), and other federal and state privacy regulations, according to the group. “We consider a broad range of legal requirements and industry best practices to pinpoint what you need to know about company policies on safety, privacy, security, and compliance,” its website says.

Common Sense has been evaluating apps and tools since June 2016. Companies receive numerical and color-coded ratings: red signifies it is not recommended; orange indicates that it be used with caution, and blue advises the educator to “use responsibly.”

Kelly said companies with products found to be lacking in some areas of compliance, based on questions considered, are given the opportunity to address any deficiencies found in their policies. “We want to make sure we engage with vendors before we publish the report,” he said. “We try to give vendors 30 days after we’ve contacted them, once we’ve identified what areas in their policy” raise red flags, he added.

After 30 days, if Common Sense hasn’t been notified of changes, the review is published with the existing ratings.

The white paper released by Common Sense focuses on the products currently on its site, and more.

“We wanted this first report to set the stage, and start a dialogue with stakeholders and the industry about improving these practices,” said Kelly. “This report isn’t calling out any vendors by name.”

Follow EdWeek Market Brief on Twitter @EdMarketBrief or connect with us on LinkedIn.

See also:

- Webinar Offers K-12 Companies Advice for Navigating Student-Data Privacy Laws

- Learning From the ‘Accidental Consequences’ of Student Data Privacy Laws

- Privacy Advocates Brace for Shakeup at U.S. Education Department

- How Companies Can Fix Ambiguous Privacy Policies

- ‘Unified Contract’ Designed to Help Districts, Companies Comply With California Law

- As States Toughen Data-Privacy Laws, Ed-Tech Providers Adjust

- Student-Data Privacy: How Parents’ Views Can Shape K-12 Companies’ Work

- Provider of ‘Connected Toys’ Vtech Settles Federal Privacy Complaint

- New Data-Privacy Realities Forcing Companies to Adjust

- State Lawmakers Balance Concerns On Student-Data Privacy

- Schools Choose Not to Delete Facebook Despite Data-Privacy Worries

Paired together the words “college” and “readiness” pack a punch in education policy circles. Few would argue against putting an emphasis on all students being well-prepared for post-secondary education. Yet when you consider the two terms in conjunction, it’s not often people think of students in middle school. It turns out, these years are far more important than previously thought.