Is the Textbook Dead? Far Too Early for Last Rites, ISTE Panel Suggests

Chicago

The title of the session on the ISTE conference’s second day was even more provocative than the headline of this post would suggest.

“The Textbook Is Extinct! Now What?” was the posted description.

In truth, the panel discussion at the sprawling tech conference was much less conclusive on that point, offering several reminders why printed texts may be likely to live with vigor in K-12 districts for years to come—despite several factors that are leading schools to become less reliant on them.

Among those factors: the ubiquity of digital academic content, including open educational resources, or materials created on licenses that allow them to be freely shared and remixed. Some districts are encouraging teachers to tap into open resources in assembling their own content piece by piece. Some providers of open resources, meanwhile, are selling to districts full-scale curricula across entire grade spans.

The panel on Monday included Ann-Marie Mapes, a state department of education official in Michigan, whose agency is developing a site to house open resources; Karen Greenleaf, the head of content for Google for Education; Adam Garry of Dell EMC (which sponsored the panel); and Jonathan Gregori, an instructional technology specialist with the Henrico County, Va., public schools.

The panel’s audience was asked to vote via mobile devices on a series of provocative questions. One was, “Should we be using the term textbook anymore?” A strong majority of the teachers, vendors, and others in attendance, in a verdict projected on a screen at the front of the room, answered no.

On another question put to them, the audience seemed to be predicting big changes for the K-12 market.

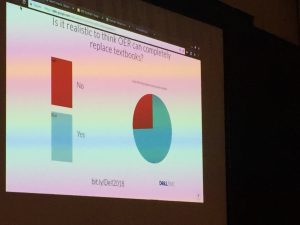

“Is it realistic to think OER can completely replace textbooks?” they were asked. The vast majority of attendees said that it was.

Some of the panelists seemed less convinced on that point, though they understood educators’ demand for changes in the market.

One of the weaknesses of textbook-centered lessons is that they make it more difficult to give students more personalized, nimble instruction, which more modular types of resources make possible, Mapes said.

“We need to stop talking about the textbook” as the center of learning, and start moving to talking about “what students’ needs are,” she said. There’s often the assumption that relying on textbooks “will meet every kid’s needs, and that’s just not the case.”

Added Gregori: “Textbooks really deliver content in one way, and not every learner learns in one way.”

Greenleaf, however, suggested that the problem is not with K-12 textbooks themselves, which as “learning objects” often offer “fabulous content.” The problem is that they are treated as one-size-fits-all resources, when the demands of districts and teachers are complex.

On the question of whether open educational resources can completely replace commercial textbooks, Mapes said it’s much more likely that both types of materials will co-exist in the market.

“Whatever textbooks evolve into will be complementary to OER,” Mapes said, adding: “We’re not going to get to 100 percent OER…There will always be space” for paid providers.

Many districts have experimented with allowing teachers to pick and choose among open resources and assemble content. But that process can be taxing, in terms of the time and devotion of resources it requires of teachers and schools, noted Greenleaf.

Textbooks, for all their shortcomings, can “level the playing field,” she said, and give districts with limited resources access to high-quality content.

Relevant Content, to Meet Students’ Needs

The questions districts face in choosing among commercial or open curricula was a topic of several sessions throughout the week at ISTE, which draws thousands of educators—as well as companies—from around the country.

In interviews, educators attending ISTE offered a variety of opinions on the future of print, digital, and open resources.

Stacey Marten, a high school librarian from the Peninsula school system in Washington, echoed the oft-heard complaint that one of the biggest weaknesses of printed textbooks is their tendency to grow stale, especially if districts don’t pay to update them regularly. Digital resources acquired piece by piece give teachers the ability to refresh classes with content that engages students, she said.

The Peninsula district uses a learning management system that houses open educational materials, said Marten, in an interview on the floor of ISTE’s exhibit hall.

“That’s one of the things I share with teachers,” she said. “‘Hey, did you know we can go right to OER to get some new curriculum for your classroom?’”

The assistant director of technology in the Peninsula district, Natalie Boyle, said open resources strongly appeal to her, because she sees a need for a curriculum to change as students’ needs and interests do.

In Washington state, districts are directed to meet academic standards in different subjects, but are also being given flexibility on how to achieve those expectations, she said. That can mean relying less on following the textbook’s script.

“Changing that perspective for teachers is a transition, but it’s best for kids,” she said. “And it ensures that learning is up to date and relevant and constantly evolving.”

Photo of slides shown during the ISTE panel on the future of textbooks by Sean Cavanagh.

Follow EdWeek Market Brief on Twitter @EdMarketBrief or connect with us on LinkedIn.

See also:

Thank you for an insightful report. Curious about OER (and other new education material formats in the US). How much do you discuss digital handwriting (and possibly also speech) as an input/interaction format? Open formats are heavily discussed also here in Finland, but in reality, the printed textbook has kept a stronger position than what was expected.