U.S. Gets Low Scores for Innovation in Education

UPDATED

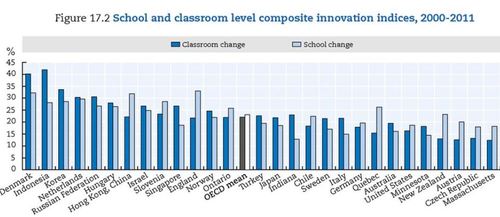

U.S. schools and classrooms rank near the bottom among the countries studied in a first-ever report on education innovation by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, or OECD.

Only the Czech Republic and Austria ranked lower, with New Zealand tying the United States in the OECD’s point system, which used data spanning 2000 to 2011. Denmark, Indonesia, Korea, and the Netherlands were found to have the most innovative educational systems.

The report, “Measuring Innovation in Education,” finds that, in general, more innovation has come from classroom practices than school practices in the countries studied over this time.

The opposite has been true in the U.S., where reformers often claim that innovative changes are not reaching the classroom. Indeed, the researchers’ findings corroborate that impression, according to Stephan Vincent-Lancrin, lead author of the study, referring to this chart as proof.

Comparing the U.S. to a country like Indonesia, which had a high innovation score, should not be interpreted as the superiority of Indonesia’s educational system. “They are trying to change a lot of things; they may have to change more than the U.S. as well,” he said, noting in an interview that the data show “the dynamic of the willingness to change.”

Comparing the U.S. to a country like Indonesia, which had a high innovation score, should not be interpreted as the superiority of Indonesia’s educational system. “They are trying to change a lot of things; they may have to change more than the U.S. as well,” he said, noting in an interview that the data show “the dynamic of the willingness to change.”

While the U.S. exhibits “very strong educational entrepreneurism,” in Vincent-Lancrin’s words, that was not part of the study. However, the report does take into account the use and availability of computers in schools. Here, he said, the U.S. is “pretty average,” not showing much change in the past decade.

Where the U.S. does stand out is in the use of assessments—a direct result of No Child Left Behind—and in the engagement of parents. In a separate, 4-page report on the U.S., the top five innovation policies and practices identified in this country were:

- More use of student assessments for monitoring school progress;

- More use of student assessments for national and district benchmarking;

- More use of student assessment data to inform parents of student progress;

- More external evaluation of secondary school classrooms; and,

- More service by parents on external school committees.

As for pedagogic practice, the top innovations found in the U.S. are:

- More observation and description in secondary school science lessons;

- More individualized reading instruction in primary school classrooms;

- More use of answer explanation in primary mathematics;

- More relating of primary school lessons to everyday life; and,

- More text interpretation in primary lessons.

Innovative pedagogic practices are increasing dramatically in all countries, in areas like relating lessons to real life, interpreting data and text, and personalizing teaching, the study’s authors found. In general, countries with greater levels of innovation see increases in certain educational outcomes, including higher—and improving—8th grade math performance, more equitable learning outcomes across ability, and more satisfied teachers.

Internationally, although many people consider education an innovation laggard, the researchers identified “a fair level of innovation in the education sector, both relative to other sectors of society and in absolute terms.” However, the speed of adoption in eduation is slower than average. The most “innovation intensity” is found in higher education.

Innovative educational systems generally spend more than non-innovative systems; however, their students are no more satisfied than those in less innovative systems. The authors found that most educational institutions included in their research have increased their per-student expenditure levels between 2000 and 2010 by similar amounts. Korea and the Czech Republic, while registering among the highest spenders, ranked at the opposite ends of the educational innovation spectrum; Korea was considered “above average” in innovation, and the Czech Republic near the bottom.

The authors acknowledge that measuring innovation in education is in its infancy, and make a case for developing an international survey that could be used to measure innovation.

“Innovation is a means to an end,” said Vincent-Lancrin. “We need to think of it not as an indicator of performance itself, but something that will translate into better educational outcomes.”

Update: This post was updated to include the countries that ranked highest on the OECD’s innovation scale.

How can we have time to innovate when all we do is test? There is a reason we stand out in the use of assessments.

In other words, all the US innovation amounts to test, test, test. No wonder we earned a low score for innovation! Other countries do not over-test students for the purposes of ranking students, schools, and teachers. Nor do most of them follow the test-and-punish model. Only the US., and apparently that’s NOT innovative. No wonder we are supposedly falling behind other nations! Real innovation will come from the real experts….teachers, not politicians, not philanthropists with a hidden agenda, and certainly not from the federal DOE.

The opposite has been true in the U.S., where reformers often claim that innovative changes are not reaching the classroom.

Implicit in this is that "reformer’s" changes are actually worthwhile. Not a particularly reasonable assumption.

http://speakingofeducation.blogspot.com/

There is no U.S. school system. There are 10k different systems. Generalizing about schooling in the USA is a waste of time and effort.

Although you’re right, those 10k district share the same obsession with national, standardized testing.

As a result of NCLB, RttT, and the CCSSI the US is now closer to a national school system than ever. It’s given our schools nationwide a more "common" direction. I believe that’s better than thousands of districts going in infinite different directions.

Yes, there are problems with some of this commonality (too much testing), but at least now students from different states have access to a higher quality public education.

The other problem arising from this move, states are starting to back away from it in fear of being compared to students from other states and being embarrassed by the results. These are the same states who fudged standards, assessments, and cut scores under NCLB. Frauds, the bunch of them and their aversion to the commonality is as transparent as can be. Again, frauds.

….which is why the salvation for SOME kids will be that the people who care the most about the success of their kids will eventually take the matter into their own reasonably well-educated hands and provide a decent education for their own kids…through home schooling, private schooling, on-line schooling, or some other option….something besides this continual lip service and educational gobbeldygook ABOUT education.

Innovative, according to the dictionary definition, only implies new and different, not better. However, proponents of favored strategies and the media use the term “innovative” to imply not just new, but better. The primary strategies in current, so-called, education reform are increased extensive testing based on national standards and opening up the public school system to competitive market forces through charter schools, increased technology investment and performance pay for teachers. Are these strategies "innovative?" Are they better? Better for what goals and for whom? If we just want more opportunities for profit, than these strategies are better. If we just want to improve the chances of a few kids to get a shot at “escaping from poverty,” then these strategies are better. However, if we want systemic improvement– improvement for all– then these strategies are a step backward. If we want an education system that values equity and respects democracy, then these strategies, may be new, but they are certainly not better.

http://www.arthurcamins.com

At Big Picture Learning, our motto is Schools, Innovation, and Influence… check us out if you want to reverse some of the trends described in this article – http://www.bigpicture.org/