Making Teacher Professional Development Decisions Based on Program Effectiveness

School leaders need better frameworks for choosing teacher professional development. A large study on the K-12 professional development space sponsored by the Bill & Melinda Gates foundation revealed that “few professional development decisions are made based on rigorous evidence of effectiveness.” This is nothing short of alarming. It is no secret that highly effective teachers can be powerful levers of student achievement at the school level. As the Coalition Of Schools Educating Boys Of Color Executive Director Ron Walker put it, “Teachers are the core technology of every school.” As such, the education community should be highly attuned to the finding that professional development—the primary tool used to improve teacher efficacy—is largely chosen without knowledge of how effective the professional development might be. What if this wasn’t the case? What magnitude of impact could be leveraged from better identifying good PD?

Spend Money on Professional Development with Real Impact

Imagine a college basketball coach who has $5,000 to spend on a training camp for his team. Chances are, this coach is not going to spend that that money on a training camp that doesn’t have a record of improving the players who participate, or a strong method of revealing how much players improved. A star coach is going to want to see that his players were exposed to new strategies and actually implemented some of those strategies. The Gates Professional Development report alludes to how PD is currently vetted noting, “As one district administrator said, to evaluate effectiveness ‘teachers fill out forms … It asks general questions like, what are some things you feel were helpful?'” As a school leader, knowing if teachers found some of the professional development topics helpful is not enough in this day and age. What school leaders need to know is the extent to which their teachers actually incorporated new strategies from professional development, within their classroom instruction. A star coach wouldn’t spend $5,000 on a training that doesn’t result in players changing their actions for the better, and neither should school leaders.

coach is not going to spend that that money on a training camp that doesn’t have a record of improving the players who participate, or a strong method of revealing how much players improved. A star coach is going to want to see that his players were exposed to new strategies and actually implemented some of those strategies. The Gates Professional Development report alludes to how PD is currently vetted noting, “As one district administrator said, to evaluate effectiveness ‘teachers fill out forms … It asks general questions like, what are some things you feel were helpful?'” As a school leader, knowing if teachers found some of the professional development topics helpful is not enough in this day and age. What school leaders need to know is the extent to which their teachers actually incorporated new strategies from professional development, within their classroom instruction. A star coach wouldn’t spend $5,000 on a training that doesn’t result in players changing their actions for the better, and neither should school leaders.

Be Ruthlessly Results-Oriented When Vetting Professional Development

The problem may be that there is a paucity of tools school leaders can use to robustly vet professional development providers. Currently, “limited information about available offerings and their effectiveness often leads decision-makers at the local level to turn to their personal networks for information about providers,” notes the Gates Report. In a landscape where there is limited research on what effective PD looks like, school leaders need to be equipped with the right questions to ask professional development providers. School leaders should be ruthlessly results-oriented when vetting providers, honing in squarely on professional development outputs.

Choose well and a school can experience substantial increases in teacher efficacy and student achievement. Choose poorly and you risk wasting thousands of dollars and countless value-add opportunities to improve teacher quality and student outcomes.

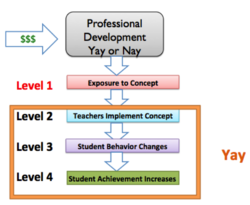

A simple and powerful professional development decision-making framework might look like this:

More Data on Effectiveness Should Equal More Willingness for Adoption

Ninety percent of teachers participate in workshop forms of professional development, which is traditionally a forum where “new” concepts are presented to teachers. Education researchers suggest that a small percentage of content actually transfers from a workshop into use within actual classroom instruction. The majority of teachers I’ve met share similar sentiments. If a lion’s share of professional development experienced by teachers simply exposes teachers to new concepts that are never implemented in the classroom, an enormous amount of time and money are being squandered on low-impact activities. Teachers are spending 68 hours a year within professional development activities, often feeling it is nothing but a compliance exercise.

In choosing professional development providers, there are a few powerful questions school leaders can leverage:

- How many concepts presented are actually implemented by the teachers you work with, and how is that measured?

- How many visible student behaviors—proxies for student achievement—change during or after you work with teachers? How do you measure this?

There is a noted lack of professional development research with methods robust enough to explicitly declare that one professional development option or another unequivocally increases student achievement. Such evidence would be akin to a flashing neon sign pointing to a level 4 professional development provider in which school leaders could confidently expect student achievement to rise upon use. What makes choosing PD so difficult is that such signs are practically non-existent. Why? Randomized control studies that produce such clear conclusions are really difficult to carry out in schools. There are few professional development providers that are effective enough to make such claims.

School leaders would benefit most by making these PD decisions based on providers’ ability to reach level 2 and level 3 of the professional development continuum. In essence, do teachers implement new or enhanced pedagogies during and after the professional development activities? Moreover, how does student behavior visibly change during or after the professional development?

Most existing professional development is already at level 1, exposing teachers to new concepts. Lets start moving towards levels 2 and 3.

See also:

- Rigorous Study Finds Actual Benefits in Immersive Teacher PD Program

- World-Class Teacher Professional Development: Neither Workshops or Rubrics

- Report: ‘Job Embedded’ Professional Development Often Found Lacking

Will Morris is the founder and CEO of EdConnective. You can follow him on twitter @EdConnective.

what is chloroquine https://chloroquineorigin.com/# hydrochlroquine