University Researcher Predicts ‘Bloodletting’ When Federal Funding Cliff Hits

The end of federal COVID relief funding is expected to bring an unprecedented shock to the U.S. education industry, according to an analysis by a researcher at Georgetown University.

And, as it draws closer, there are concerns that education companies aren’t grasping the full reality of what’s to come.

In a recent webinar, the university’s Edunomics Lab explored exactly how destabilizing the federal funding cliff will be after the September 2024 deadline for obligating funds hits, and what actions it could force districts to make.

The 2024-25 school year will be a “bloodletting” for the education industry, said Edunomics Lab Director Marguerite Roza during the virtual presentation.

Over the last two years, K-12 education has seen an additional $23 billion spent annually on nonprofits and commercial organizations, Edunomics Lab reports, including a $8.5 billion increase in spending on purchased services and another $8 billion increase on supplies, Roza said. In total, the three rounds of stimulus pumped around $190 billion into public schools.

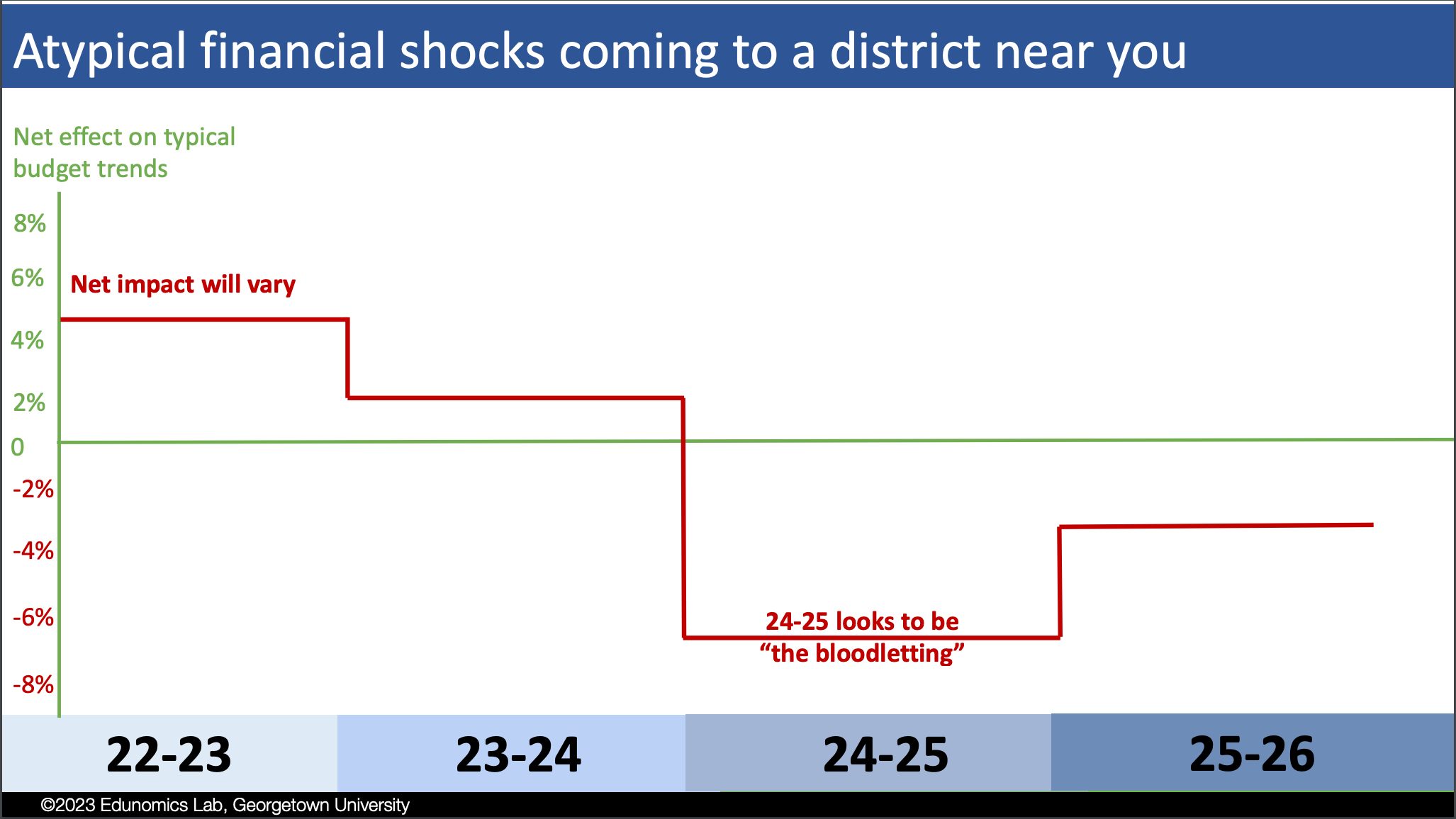

Placing the impact of the stimulus on a graph along with other economic factors, the flow of dollars had around a 5 percent positive shock in 2022-23 — a big boost for the sector, Roza said. The following year, in 2023-24, its impact remained positive, around 2 percent above baseline.

In the 2024-25 school year, however, the end of the money is expected to have a negative impact, dropping more than 6 percent below baseline budget trends.

“I know [saying ‘bloodletting’] is gory, dramatic language,” Roza said. “We are trying to get people’s attention that this is a financial shock to the K-12 system unlike any we’ve seen before.”

In reality, that means districts will need to swiftly take steps to slash costs in order to attempt to avoid reducing staff — a step that history shows is always district’s first priority, Roza said.

In previous recessions, contracts with vendors have often been the first items to be cut, she said. Districts typically start with actions such as allowing contracts to expire, postponing maintenance, and even eliminate professional development days.

But the reality is that labor reductions, which are disruptive for schools and students, also bring significant savings.

“This is going to get very tricky for districts, so that’s the big tension here,” she said. “It’s labor versus any spending on nonprofits or vendors.”

At Tucson Unified Schools in Arizona, for example, a committee of top administrators went through the process of paring down stimulus-era purchases last year, which included whittling down to about eight software pieces that will continue going forward.

Next, the district is starting the process of deciding which staffing decisions to keep, which includes pulling student achievement data to evaluate which positions are having the greatest impact on mitigating learning loss, said Tucson Chief Financial Officer Ricky Hernandez.

The district ended up investing around 80 cents of every stimulus dollar on people in some way, shape, or form, Hernandez recently told Market Brief, with the understanding that the positions were temporary.

“We know that this federal funding has a very specific lifespan,” Hernadez said.

And once that money goes away, sustaining all of these jobs is something that, unfortunately, the district is not in a position to do.”

The cliff isn’t here, yet. There’s still money to be spent before the deadline. Especially in Nevada, Rhode Island, Wisconsin, and Vermont, states where Roza says districts have been slower to allocate the dollars. She expects school boards to take their last votes on how to spend remaining dollars in May and June.

I know [saying ‘bloodletting’] is gory, dramatic language. We are trying to get people’s attention that this is a financial shock to the K-12 system unlike any we’ve seen before.Marguerite Roza, director of Georgetown University's Edunomics Lab

After that, vendors should be preparing to make their case for why their product is worth keeping to both districts and, in the event that state legislators look to try to soften the financial blow for K-12 systems, to lawmakers. (State funding typically makes up about around 47 percent of public school districts’ budgets, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.)

“We would urge nonprofits and vendors to ensure you have data that shows the value of what you’re doing for students,” Roza said. “A lot of leaders at state and local level looking for where we have evidence.”

Image: iStock/Getty

Follow EdWeek Market Brief on Twitter @EdMarketBrief or connect with us on LinkedIn.

See also: