New Federal Ed. Law Opens Door to Investors, Including Private Companies

A provision in the Every Student Succeeds Act supports a relatively new approach to investing in public education, one in which private and public entities that pour money into school programs can get financial rewards if they show results.

The law calls those efforts “pay for success” initiatives. It’s a concept that has been tested in different areas of government, including with public preschool students in Utah, where it has generated controversy.

The basic idea in pay-for-success projects, sometimes called social-impact bonds, is to allow private investors and other entities to devote money to fixing a problem or focusing on an issue in the public sphere. In theory, the arrangement costs taxpayers nothing, because the investor is covering the costs. And if savings to taxpayers result from the policy change brought about, the investor can recoup a profit.

The pay-for-success language is included in section of Title I of the law supporting prevention and intervention programs for youths, as well as in Title IV of the law, which authorizes block grants to state and local education agencies to support student safety and health. Pay for success is just one of many options grant recipients can choose.

The law defines pay for success as a “performance-based grant, contract, or cooperative agreement awarded by a public entity in which a commitment is made to pay for improved outcomes that result in a social benefit and direct cost savings or cost avoidance to the public sector.”

The language says that projects have to include a feasibility study describing how the proposed intervention is “based on evidence of effectiveness.”

Pay for success efforts also must include a rigorous, third-party evaluation to determine whether the project is meeting its goals; an annual report on progress; and an assurance that payments are made only when the agreed-upon results are achieved.

Another section of the law appears to define the entities that can participate, to include not only businesses, but nonprofits, community-based organizations, and higher education entities. Congressional staff for both Democrats and Republicans involved in drafting the law confirmed that investors can include for-profit, as well as non-profit, and public entities.

One of those staffers noted that the law requires those investors to have “a demonstrated record of success in implementing [those types of] programs and activities.”

It’s unclear how many states or districts will be interested in partnering with public schools — or what types of education projects they would focus on.

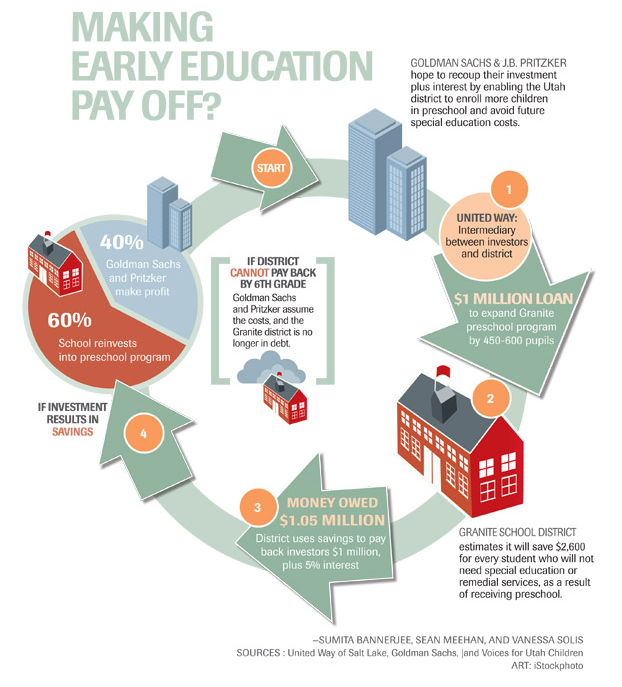

But two years ago, EdWeek reported on a pay-for-success project in Utah, in which Goldman Sachs and the investor J.B. Pritzker agreed to bankroll the expansion of the Granite school district’s preschool program. The goal was to reduce the number of students who later needed special-education services–which would, in theory, bring savings to taxpayers.

The EdWeek graphic, below, depicts the way the flow of investment in Utah is designed to play out.

But from the beginning, some education advocates and school-finance officials raised concerns about the Utah project, particularly how success would be measured and financial returns doled out.

Those worries ramped up this fall, after Utah officials announced that the project had helped more than 100 children avoid special education. The claim was that nearly all of the children the project had been working with avoided entry into special-education, a rate which resulted in a $260,000 return to Goldman Sachs, the New York Times reported.

But the Times report also said the paper had spoken with nine early-childhood experts who were skeptical of the Utah program’s claims.

One of their worries was that even well-funded preschool programs typically reduce the portion of students needing special education by only 10-20 percent–or 50 percent, tops–making the Utah results seem improbable.

In addition, those early-childhood advocates said it was wrong to assume that many children in the program would have needed special education later in their academic careers. If that assumption was faulty, they said, it raised the possibility that Utah officials could be overstating how many students were helped through the effort–inflating the results–and the profits for Goldman Sachs.

As ESSA moved through the legislative process, the pay-for-success provision drew scorn from a number of online critics, particularly those wary of commercial interests reaping rewards from public schools.

The proposal “should not be about creating capital opportunities for Wall Street or a marketing scheme for tech companies,” read one post sounding those objections.

Congressional staff from both parties told EdWeek that the pay-for-success provision was one of many options for states and local districts spending money under the law. They also said the protections in the law would ensure that grant recipients are held accountable for results.

“State and local leaders have the voluntary option to use funds to establish pay-for-success initiatives, so long as these initiatives meet broad parameters intended to ensure the efficient and effective use of taxpayer dollars,” said Lauren Aronson, a spokeswoman for the Republican majority on the House Education and the Workforce Committee, in a statement.

“These provisions provide state and local leaders more flexibility to develop innovative programs that will best meet the needs of their communities.”

Questioning the Metrics

The pay for success concept is only a few years old; only eight such projects have been launched to date, said Nicole Truhe, the government affairs director at America Forward, an organization that supported the provision’s inclusion in ESSA. America Forward is the nonpartisan policy division of New Profit, a venture philanthropy fund.

Pay-for-success provisions have been included in other areas of federal law, including the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act; the transportation law known as the FAST Act; and in helping former prisoners with re-entry into society through the criminal justice system, Truhe noted.

“We believe pay-for-success can be a tool that sectors use–in this case, the education system–to create access to successful innovations,” Truhe said in an interview.

But the inclusion of the provision was opposed by the Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates, Inc., which advocates for students with disabilities and their families.

The organization said policymakers should be wary of using the sort of metrics for success that were relied on in Utah. Simply reducing the number of children receiving special education services is not necessarily a good thing — and is harmful, if it turns out those children could have benefited from that help, said Denise Marshall, the organization’s executive director.

Marshall said her organization pushed for federal lawmakers to include the language to ensure that third-party reviews of the pay-for-success programs are conducted. But even that safeguard does not assuage her worries about the thrust of the program.

Judging success of students who may have been considered for special education should focus on “is the gap being lessened for them and is there a successful academic outcome,” Marshall said. “Governments should not be incentivized for failing to serve students.”

See also:

Thanks to this article I can learn more. Expand my knowledge and abilities. Actually the article is very real.