Schools’ Activities to Raise Money With Businesses Don’t Pay, Researchers Say

School districts that boost their coffers by entering into money-making agreements with companies rarely gain much in return, a pair of researchers found.

“Every dollar is important, but every dollar might not be worthwhile,” said Brian Brent, a professor and associate dean at the University of Rochester in New York, in a phone interview about the findings of the study he summarized this month in School Business Affairs, a magazine published by the Association of School Business Officials International.

While Brent acknowledges that money is raised by districts engaging in a variety of commercial activities with beverage companies, local businesses, and national companies, he said its impact is marginal, and the cost of administering and maintaining such contracts is seldom factored into the equation.

School business officials in 197 Pennsylvania districts and 307 New York districts responded to the survey. Brent and his co-author Stephen Lunden, the assistant superintendent for administrative services at the Maryvale Union Free School District in New York, found that 94 percent of Pennsylvania schools and 75 percent of New York schools engaged in some sort of commercial activity.

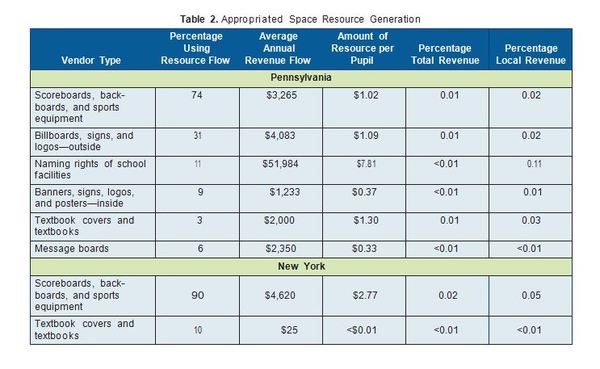

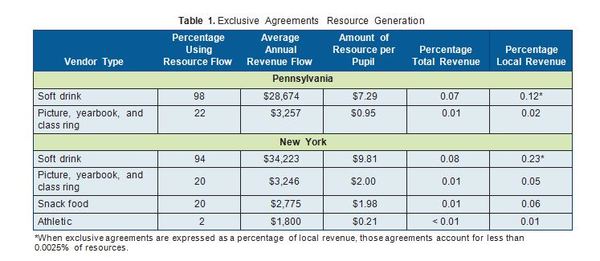

Their study focused on two primary forms of making money: granting exclusive agreements to sell or promote products or services, including agreements to offer vending machines and so-called “pouring rights” to soft drink and beverage companies, and appropriated space agreements, in which districts may sell space on school property from scoreboards to buses and computer screens.

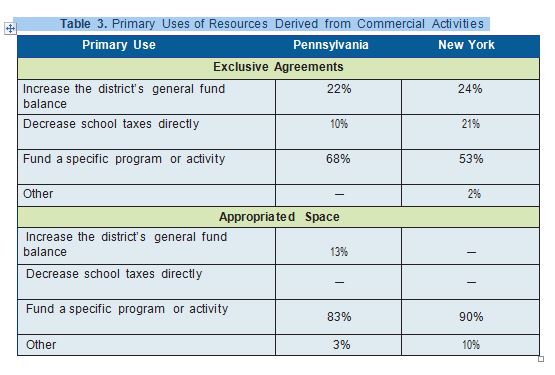

Brent and Lunden compared the money raised with how much it impacts local tax revenues, and found the impact to be negligible, as the tables above and below show. However, that is often the reason cited by districts for engaging in these activities—to offset losses in local tax revenues.

“School business officials want to help,” he said, looking for alternate sources to raise revenues and to provide tax relief. But he said the numbers don’t add up. This study is a “cautionary tale” that the efforts might not be worth the potential down side, which includes exposing children as a “captive audience” to the commercial messages, and promoting unhealthy products, among others, Brent said.

The researchers also asked districts to explain how they applied the funds they raised. Usually, the money was intended to provide funding for a specific sport or extracurricular activity.

The researchers also asked districts to explain how they applied the funds they raised. Usually, the money was intended to provide funding for a specific sport or extracurricular activity.

Most district officials said they would continue to use exclusive agreements—59 percent in Pennsylvania and 51 percent in New York. But opinions differed more markedly on the use of appropriated space: 40 percent of New Yorkers said they intended to continue to pursue this method of getting income, while 74 percent said they would not.

The study was originally published in Leadership and Policy in Schools on July 13, 2009 under the title, “Benefits and Costs of School-based Activities.” Brent said he does not think the results would have been much different had the study been conducted more recently, since he continues to see headlines about districts entering into such contracts. “I’m an ex-CPA, so I recognize generally that with revenues there are costs,” he said. “In reading an article that says there’s a $1.5 million contract, I know the way to think about that is ‘over the life of the contract’,” he said.

Brent acknowledges the pressure districts are under to get better results with budgets that are tight. “It’s going to be continual issue for school districts striving to meet increasing demands, constrained not necessarily by the economy, but by local and state governments about what’s perceived to be high levels of spending,” he said.

Michael Griffith, the school finance consultant for the Education Commission of the States, agreed, saying he hears this from school districts across the country. “It’s a decision school principals and superintendents have to make: is it worth it to raise these funds, and what are they going to use it for, or does it make sense to go to the voters,” he said.

While the alternative revenue tends to be very small, Griffith maintains that districts would view it as important. “Twenty years ago it was simply money you went out and raised to buy equipment like swings and jungle gyms. Now, in some districts, it’s used for hiring librarians and music teachers,” he said.

Source: These graphs originally appeared in the September 2014 School Business Affairs magazine article ‘Pennies for Perils? An Accounting of School-Based Commercial Activities’ by Brian O. Brent, Ph.D., and Stephen Lunden; they are reprinted with permission of the Association of School Business Officials International (ASBO). The information herein does not necessarily represent the views or policies of ASBO International, and use of this imprint does not imply any endorsement or recognition by ASBO International and its officers or affiliates.

hank you so much for this. I was into this iss https://vidmate.onl/download/ ue and tired to tinker around to check if its possible but couldnt get it done. Now that i have seen the way you did it, thanks guys with regards