Brookings Institution Researchers Find Many Countries Lack High-Quality Education Data

For education companies eyeing business in new foreign markets, getting good data–on student enrollment, academic achievement, school spending–can matter a lot. In many developing countries, however, getting good education data is far from easy.

Researchers at the Brookings Institution’s Center for Universal Education recently examined public online information from low- and middle-income nations to get a sense of the availability and usefulness of the school-level data they make public.

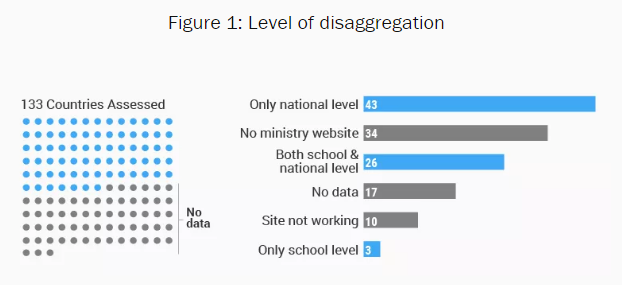

Of the 133 countries the researchers examined, nearly half had no available data, either because the government education agencies did not have websites, or the relevant information was missing or a chore to access, the authors explained in an online post,

Of the other 72 nations, 43 had data only at at the national level, which was not disaggregated. That left just 29 countries with sufficiency disaggregated data at the school level, explained the authors of the post, Lindsay Read and Tamar Manuelyan Atinc.

The Brookings authors see having good data available as essential to making government work transparent, empowering parents and students, and improving the quality of education in developing countries.

In wealthy nations, making data transparent can be as simple as making rich existing data sets open to the public. But in developing countries, the data-collection process often has to be overhauled for data to be made useful, they explain.

In some countries, data are collected in ways that make it difficult to crunch, because they come in PDF form or other formats that can’t be read digitally.

The following graphic from the post by Read and Atinc shows the extent of the limitations of the data in the 133 countries they looked at:

The authors also found that when data were available on education spending on the countries they studied, the information was focused on the funding for school systems, not what was actually being spent.

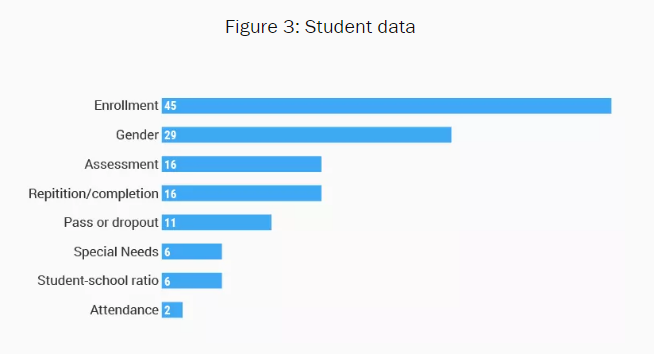

They also found that the data collected tended to focus on student enrollment numbers, rather than data more closely associated with school quality. Here’s the Brookings breakdown of the information various nations were collecting on that front:

Not all the countries the authors examined were poor-performers when it comes to providing rich public data. They cite an eclectic group of countries–including India, Lebanon, and the Phillipines–that provides a relative abundance of educational information.

India, for example, offers report cards on individual schools with detailed tables about test results, school facilities, and other information. And Lebanon’s Ministry of Education, the authors point out, provides a navigable table for evaluating individual schools, classroom characteristics, and teacher-licensing information.

For more information on the work of Read and Atinc on the availability of education data, see this related post on lessons they’ve learned from studying the information flow in developing countries.

See also: