Harvard Researchers Envision Better Business, Nonprofit Cooperation in K-12

Many of the ambitious efforts made by nonprofits and businesses to improve K-12 education are derailed by lack of coordination and cooperation among those organizations, argues a new report by researchers from the Harvard Business School.

The authors call for a better-organized approach to delivering social services and other programs—a strategy they describe as “collective impact,” which is being tested to varying degrees in communities around the country.

Authors Allen S. Grossman and Ann B. Lombard, both of the Harvard Business School, focus on many of the social-service supports that they say can lift students out of poverty and contribute to their success in school. That assistance includes tutoring, mentoring, counseling, and access to health care.

In many communities, the impact of those services is stymied by different organizations’ work not meshing with each other, according to the report.

“[I]n the typical town or city, each nonprofit addresses only one part of a highly interrelated education system,” Grossman and Lombard explain. “The nonprofits seldom collaborate with each other, rarely share common goals, and measure outcomes inconsistently.”

The result is “service delivery chaos,” the authors say. “Some services are duplicated, others are missing, and great providers do not displace poor ones.”

As an alternative to that disorder, Grossman and Lombard argue for districts and communities trying collective impact strategies. Those approaches are generally defined as attempts to marshall the different efforts of various service providers—including government, business, and nonprofits—around common goals, and, above all, a clear and unified plan for executing on those missions.

Their report is based on interviews with 70 business officials and leaders who’ve attempted to put in place collective impact strategies; as well as on a survey of those individuals.

Shared Strategies, Metrics

Collective impact, as defined by Grossman and Lombard, tries to change how services are delivered for alleviating poverty, by encouraging providers to work together to align their activities around goals, using common metrics to measure progress, and put in place and improve upon good practices.

The authors trace the idea to the early 2000s, but say it was given a formal name by John Kania and Mark Kramer in an article published in the 2011 Stanford Social Innovation Review.

There are several factors behind the disorganization that permeates much of businesses’ and nonprofits’ work in education, Grossman said in an interview. Many nonprofit leaders spend more than half their time scrambling to raise money, not engaging in long-term planning, particularly when it involves peer organizations, he said.

“Survival is paramount to them,” said Grossman, and better “coordination does not address survival.”

Another barrier to cooperation: Collecting data on the results of the work on nonprofits involved in providing social services is difficult. So is forging strong, lasting partnerships between organizations, he said. “It takes a lot of work to get people to work together,” Grossman said, and too often that work ends up being “no one’s job.”

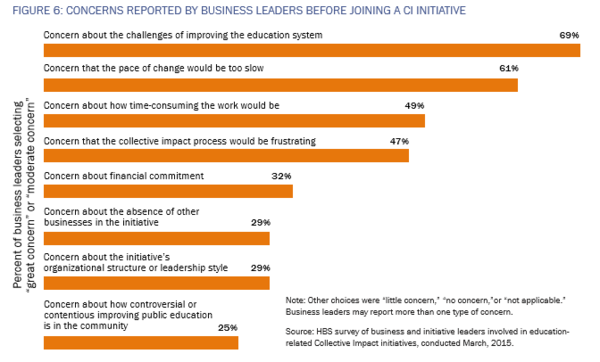

Business officials are eager to work in their local communities, the survey accompanying the report finds. Their biggest concerns about putting in place a collective-impact strategy are doubts about whether they can bring change to the system, and worries about the slow pace of change.

Only about half of private-sector officials were worried about how time consuming that work would be. See the full poll results, below:

Grossman, is a senior fellow and retired professor of management practice at Harvard Business School, who has studied the work of nonprofits extensively. He served as president and CEO of Outward Bound USA, and also served in executive roles in the private sector.

How prevalent are “collective impact” models today? The report says that it sees signs of the approach being used in 145 communities, though it depends on how one slices it. Grossman said a smaller number of communities, perhaps 70 or 80, have taken steps toward implementing the model, but a much smaller number, roughly 20 to 25, have taken concrete steps to promote coordination among nonprofits and businesses.

In order to bring collective impact models into reality, communities typically need an organization to take a lead role, or provide the “backbone” for coordinating work among different organizations to improve schools, Grossman said.

That organization could be a startup player or an established entity, he said—but it has to be respected within the community, and it can’t be regarded as dispensing top-down advice.

The authors cite specific examples of communities implementing what could be considered collective-impact strategies.

One of them has played out in the Salt Lake City region, where a United Way chapter has helped lead efforts to create better coordination between schools and social-service providers, according to the report.

In Cincinnati, corporations such as Procter & Gamble and GE have been heavily involved in helping schools set objectives for academic achievement, the authors say.

The work that goes into putting a collective-impact effort together is in many respects more complex and ambitious than other strategies that have been tried to overhaul schools by other means, Grossman said. It doesn’t rely on a single idea, he said, but a series of them working together.

Collective impact is “harder than going to the next silver bullet that comes along—we have decades of proof that [taking that approach] doesn’t work,” Grossman said.

While “it’s easy to be skeptical,” of getting various organizations to work in tandem, he added, if they do, “it has the possibility of bringing about a transformation.”

My concern, as is also the concern of many professional educators and educational researchers, is how and if these private organizations are listening . . . just simply LISTENING to TEACHERS–NOT school board members, NOT so-called "reformers" (code for "destroy the public schools at all costs and with lies"), NOT Arne Duncan, NOT Bill Gates, NOT Michelle Rhee, NOT the Walton Family, NOT ALEC, NOT the local chamber of commerce–listen to TEACHERS because they KNOW what children and adolescents need. Plus, if these private organizations really cared about schooling, they’d lobby in Washington, DC and every state house across the U. S. for greater policies that have an impact on reducing poverty–such as higher minimum wages and free health care for ALL Americans. Teaching is NOT a business for many reasons; but primarily because educators CANNOT alter the raw materials they work with BEFORE they come to school each day. We take children from where they are and move them to another place cognitively, socially, emotionally, physically (with physical education and recess), and with their maturing identities. We can’t control those raw materials, we just meet them where they are and take them to the next level with extremely limited resources compared to private industry; and we do it with amazing success! See the book, Why America’s Public Schools Are the Best Place for Kids: Reality vs. Negative Perceptions for research on how businesses can help and NOT harm teachers and children.

Once again, we see people trained as economists attempting to prescribe what ought to be done in public schools. Having failed to make positive changes in the American economy…except for the 1%…they turn their attention to raiding the trillion dollars a year spent on public schools. That is what this "cooperation" is all about. It has nothing to do with raising achievement levels across the board and making every high school in the country as successful as the public schools in Massachusetts…where the folks making the key decisions have learned to by and large ignore the "advice" of Harvard Business School.

Corporatve involvement in public education is disastrous from start to finish. Corporations have only one goal and that is to privatize pub;ic education to the benefit of greedy organizations. They desire only to train minimum wage employees with public school funds.

The Business School conclusion of "service delivery chaos" would have also been an accurate label for public education in this country prior to education reform, heck, even post ed reform. Implementation of many of the reforms has been a pell mell effort, at best. First the states went in fifty different directions under NCLB, then, under Common Core State Standards, some are on board, some not…with the standards, then with the two consortia assessments. It’s borderline comedic except it’s not funny. It continues to be an embarrassment and the biggest losers are our students.